I still remember the first Dune movie’s opening scene. Instead of jumping into the labyrinthine politics of House Atreides and the Imperium (as is the case in the book) we see the Arrakis’ natives, the Fremen, fighting to liberate their homeward from its oppressors. The change seemed to signal that the movies would pay additional attention to the Fremen, treating them as real characters with agency and motive, not like original book’s careless Middle Eastern copy-paste.

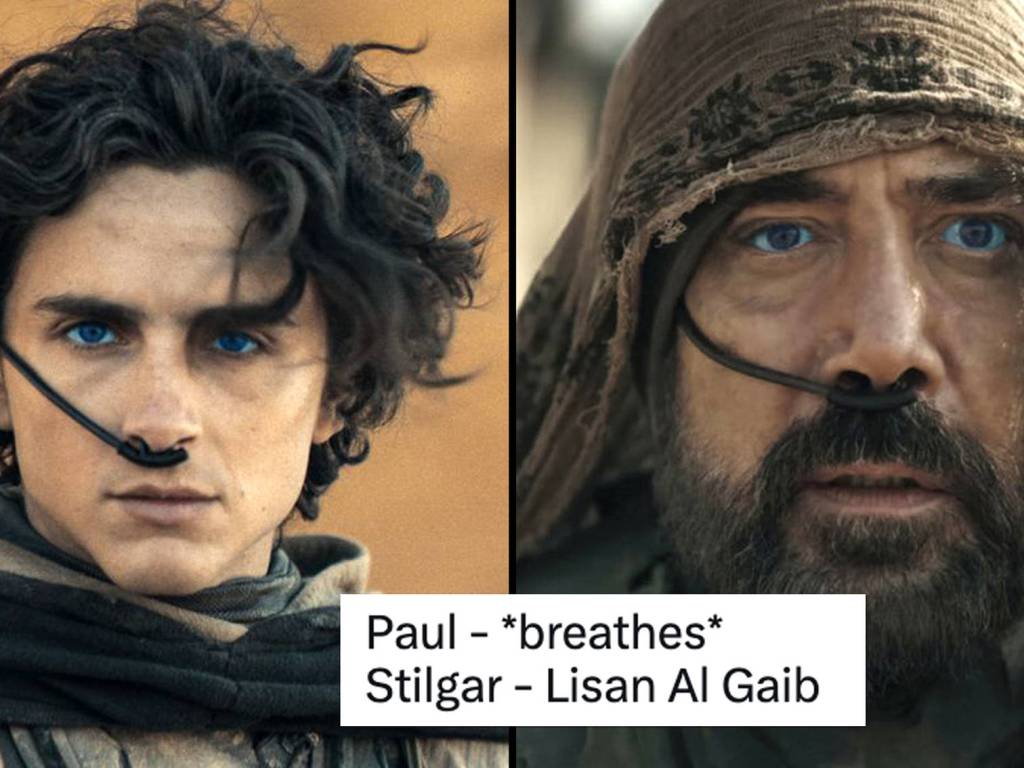

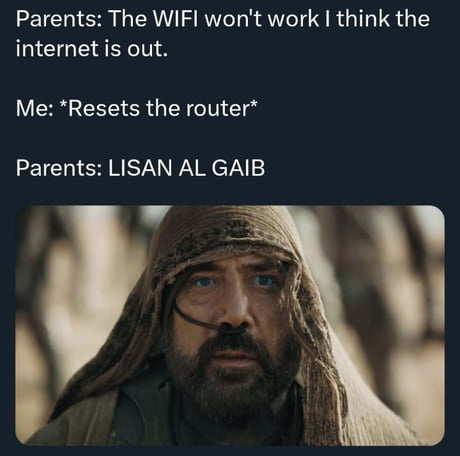

I loved many parts of Dune: Part Two, but the first film’s promise turned into the second movie’s biggest weakness. The Fremen in Part II are overwhelmingly described as “fundamentalists” and almost immediately fall to their knees worshiping Paul Atreides. Instead of addressing some of the problems with Dune author Frank Herbert’s Fremen, the movie offers us an even more simplified and unsympathetic depiction. In doing so, it takes what should be a great tragedy, the conversion of the Fremen into fanatics, and makes it into comic relief. I’m not against humor (especially in a three hour movie) but couldn’t Villeneuve have made jokes about literally anything else?

Stilgar

To understand how Villeneuve’s Fremen differ from Herbert’s Fremen, we should take a look at the most important Fremen character in Herbert’s book. It’s not Chani, but Stilgar.

To Villeneuve, Stilgar is a flanderized fundamentalist fanatic who more or less instantly declares Paul the Lisan al-Ghaib. Herbert’s version, on the other hand, is far more sympathetic. Stilgar is a famous Fremen leader who instantly impresses Jessica with both his strength and his wisdom.

“What is his ancestry? she wondered. Whence comes such breeding? She said: “Stilgar, I underestimated you.”

“Such was my suspicion,” he said.

Stilgar also has a close relationship with Paul. Indeed, at times it resembles a father/son dynamic.

“The one who led Tabr sietch before me,” Stilgar said, “he was my friend. We shared dangers. He owed me his life many a time … and I owed him mine.”

“I am your friend, Stilgar,” Paul said.

“No man doubts it,” Stilgar said.

Over the course of the story, Stilgar changes just as much as Paul does. Stilgar comes to trust Paul, and sees him more and more as the promised messiah. Eventually, he begins to take orders from Paul. Only in the very final chapter, however, does Stilgar complete his journey.

“Water from the sky,” Stilgar whispered.

In that instant, Paul saw how Stilgar had been transformed from the Fremen naib to a creature of the Lisan al-Ghaib, a receptacle for awe and obedience. It was a lessening of the man, and Paul felt the ghost-wind of the jihad in it.

I have seen a friend become a worshiper, he thought.

That line is a gut punch because we’ve come to value the friendship between Paul and Stilgar. It’s the saddest part of the story, in many ways the emotional climax.

Instead of Stilgar, Denis Villeneuve makes Chani the most important Fremen character. I actually really like Chani’s story in the movie, but there’s a key difference. Chani’s rejection of Paul’s authority makes her an exception, while Stilgar’s journey to accepting Paul is representative of the Fremen as a whole. Chani’s story might make for great drama, but it still leaves the rest of the Fremen looking like idiots (just look at the memes above).

Religion and Nature

Why do the Fremen turn from fiercely independent warriors to servants of Paul? The movie would have us believe that it is because of the prophecy of the Lisan al-Ghaib, a vaguely defined chosen one. There is some truth to this. In the book, the story of the Lisan al-Ghaib comes from the Missionaria Protectiva, a branch of the Bene Gesserit specializing in spreading similar myths to primitive planets in the hope of making them easier to control. However, that is not the whole story.

In the book, the Fremen do not follow Paul out of some vague, pre-programmed code, as though they’re clones ordered to execute order sixty-six. The Fremen want something very specific out of Paul. They want to terraform Arrakis. Decades before the start of the main story, when the father of Liet Kynes (the planetologist from the first movie) arrived on Dune, he revealed to the Fremen that it would be possible to turn Arrakis into a wet, habitable planet within a few centuries. The Fremen immediately get to work. The Fremen, in other words, are just as interested in the environment as they are in religion.

The environmental theme is present in Villeneuve’s, movie, but only in a few blink-and-you-miss-it lines of dialogue. Instead, the main nuance of the Fremen position is that the northern Fremen are wary of Paul, while everyone takes for granted that the far more numerous southern Fremen “fundamentalists” will immediately embrace Paul as their savior. Making the Fremen worship Paul simply because of who he is, rather than what he plans to do, does a disservice to them.

The movie’s interpretation does away with an important idea from the books. “When religion and politics ride the same cart, when that cart is driven by a living holy man (baraka), nothing can stand in their path.” In other words, religion by itself is not an overwhelming force. It can only reach a tidal wave when paired with specific political goals. In the book, the final chapter involves Stilgar dreaming of Arrakis as a watery paradise. At the end of the movie, on the other hand, Paul just orders the Fremen to “lead [my enemies] to paradise,” meaning simply, “kill them all.”

In short, Dune isn’t just about the ways religion can be manipulated. It also has a lot to say about how people interact with nature. And the weird part is, Denis Villeneuve knows this. In an interview just before the release of the movie, he recalled the first time he read the book.

I discovered the book in my teenage years, and I remember being totally fascinated by its poetry, by what it was saying about nature—the true main character of Dune,” he recalls. “At the time, I was studying science, I thought I could become either a filmmaker or a biologist, so the way Frank Herbert approached ecology in the book for me was so fresh, so rich, so poetic, so powerful.

Denis Villeneuve

Somehow, through the thousand-step process of turning an idea into a $100 million dollar movie, that idea was almost completely eroded away.

I’m not here to say that the book is always better than the movie. Frank Herbert’s portrayal of the Fremen was far from perfect. It’s no secret that he stole virtually the entire Fremen language, Chakobsa, from Arabic. Some words come straight from Arabic, often translated from nonsensical phrases, “Lisan al-Ghaib,” for example, means “tongue of the unseen.” You could get away with a lot more in the 1960s. The movie actually improved on things by making Chakobsa a complete language with original terms. But I can’t help but feel as though Villeneuve missed the forest for the trees.

Dune is, at least in part, a story abut how religion can be used to control people. But if that’s the message, isn’t it better to show normal and nuanced people being controlled? Why not show the Fremen in a more sympatheic light? Or at least show how other non-Fremen characters are also motivated by religion (as Dr. Yueh was in the book). Otherwise it’s not a story about how religion is powerful, it’s about how those desert people are suckers.

I don’t want anyone to walk away thinking that I hated Dune Part II. There’s a lot to like. It seems as though Villeneuve’s movies will go down as the “definitive” version of the Dune story. I only wish that the Fremen got the same care and attention that Denis Villeneuve lavishes upon the rest of the story.