It’s a good time to be a science fiction fan. As Denis Villeneuve’s Dune Part II releases to critical acclaim and a sandworm-sized box office haul, it seems that the genre has finally risen from the realm of comic-cons and giganerds like me and into the mainstream. Yet many people still haven’t given the genre its full credit. History shows us that far from just spinning entertaining yarns, science fiction has the power to literally remake the future it claims to represent.

In general, observers tend to view science fiction stories as one of two things. They can either be glimpses of a possible future (think of how people still express fears of George Orwell’s 1984 becoming reality) or reflections of the historical moment in which they were produced. Dune almost always gets lumped with the latter. People are more interested in seeing Dune as a kind of allegory for the present day than a picture of the future. Competition for the spice in Frank Herbert’s original 1965 Dune book, for instance, clearly mirrors the real world’s ruthless struggle for oil, and the specifics of the book’s plot draw heavily from the adventures of Lawrence of Arabia during World War One. More recently, other critics have drawn comparisons between Denis Villeneuve’s Dune and the Iraq War. None of this should surprise anyone. It’s to be expected that writers should draw on their own beliefs and experiences. However, focusing on the origins and inspirations of science fiction shouldn’t overshadow the genre’s ability to predict the future.

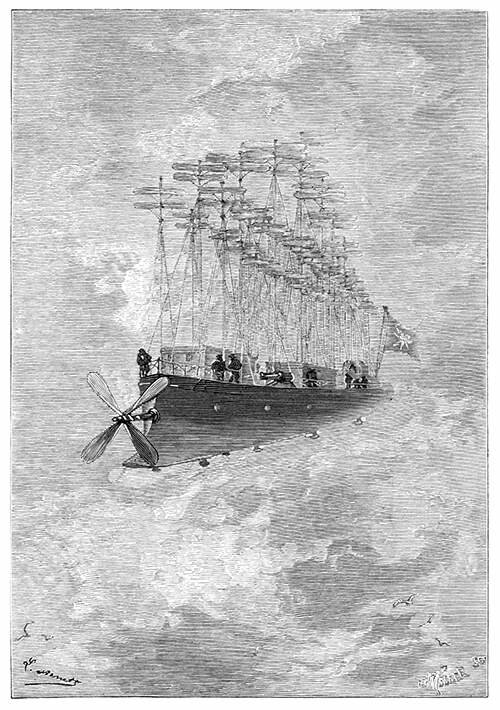

Despite inevitably taking inspiration from the past, science fiction can actually prove surprisingly prescient. Consider, for example, Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870), which takes place on a sophisticated and (at the time) entirely fantastical submarine. Within a century, however, Verne’s ideas would become reality. Another Verne novel, The Clipper of the Clouds, depicted an airship kept aloft by dozens of horizontal propellers, a predecessor of the modern helicopter. Most ominously, in 1914, H. G. Wells wrote The World Set Free, a story involving a global war of immensely destructive “atomic bombs.”

How is it that science fiction can be so uncannily accurate? Perhaps Jules Verne and H.G. Wells were visionaries, capable of seeing the future more clearly than others. But I think another part of the story is more interesting. Sometimes, books become so popular that their vision of the future is taken as fact. In other words, science fiction writers can create the future merely by the act of predicting it.

The list of innovators whose creations were influenced by science fiction goes on and on. Clipper of the Clouds inspired a young Igor Sikorsky to built his first model helicopter. In the 1930s, physicist Leo Szilard read The World Set Free and soon after discovered the nuclear chain reaction. Later, he would become one of the founders of the Manhattan Project. Even Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity was inspired by stories he’d read from nineteenth century German author Aaron Bernstein.

As befits an actor, Ronald Regan was a particularly avid consumer of sci-fi. After a screening of The Day After, a sci-fi film imagining the catastrophic effects of a nuclear war, Reagan was badly shaken, and later credited the film for changing his views on nuclear war. In turn, Tom Clancy’s Red Storm Rising (depicting a non-nuclear war between the United States and Soviet Union) reinforced Ronald Reagan view that the US military had to be ready for a conventional war. He recommended the book to Margaret Thatcher, describing it as “an excellent picture of the Soviet Union’s intentions and strategy.”

Unfortunately, sometimes science fiction can push leaders down disastrous paths. When Japanese Admiral Yamamoto read Hector Bywater’s Great Pacific War (1925), he was inspired by its depiction of Japanese victories against the superior American navy. The book soon became required reading for Japanese officers and may have contributed to Imperial Japan’s disastrous decision to declare war on the United States. In the end, the war described by Bywater had almost no resemblance to the one that actually played out between 1941 and 1945.

Clearly, commentators have to treat science fiction as more than just a metaphor for modern issues. Great science fiction has the potential to not only explain the present, but to shape the future. But here’s the paradox: science fiction can only influence the future by resonating with readers in the present. Readers from Albert Einstein to Isoroku Yamamoto have always been attracted to fiction that plays on pre-existing themes, novels that reference contemporary events in the same way that Dune so unapologetically taps into Middle East politics and twentieth century economics. To impact the future, science fiction must root itself deeply in the past and present.

Put simply, science fiction turns all of its readers into Paul Muad’dib, able to synthesize past, present and future in one spice-fueled vision.