“Do you see that map, Maximus? That is the world which I created.”

Gladiator, 2000

To modern audiences, the borders of the Roman Empire hold an almost mythical status. As the General Maximus says in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator, “I’ve seen much of the rest of the world. It is brutal and cruel and dark. Rome is the light.” Fortifications like Hadrian’s Wall are often (and inaccurately) portrayed as the line dividing civilization from barbarism. Some self-described historians even claim that the invasions during the decline of the Roman Empire stand as proof that no state can survive without rigidly defended borders. However, Romans did not think of the empire in terms of borders and hard boundaries.

The inaccuracies start with the scene’s map. The map in Gladiator doesn’t look like anything that would have actually existed in the Roman Empire. It is often said that Romans didn’t use maps at all, but that’s not entirely true. Romans were very good at drawing city plans, and meticulous in dividing up land for use by retired soldiers (centuration). Romans, however didn’t make large-scale geographic maps.

The lack of large maps might sound strange. After all, the Romans had an enormous empire to administer, and were famously fastidious about logistics and organization. Had they wanted a map of the sort shown in Gladiator, they certainly possessed the technical ability to make it. So why didn’t they? Well, because they didn’t perceive their empire in the same way we do.

Maps may seem like an objective account of the world around you, but they aren’t. Who says north is up? Why do maps have to be rectangular? We use these kinds of shorthand conventions it’s what we’re used to. What’s more, one map can only provide a very specific set of information. If you want go hiking in the Alps, a given map of the area might range from essential (topographic map) to useless (political map). For their part, the Romans’ favorite type of “map” was an itinerarium, basically a long list of town names and the distances between them on the main roads. Itineraries were essential for any long distance traveler. So long as you stayed on the roads, they could give you a clear idea of how far it was to your destination, how many mile you had already traveled, and where the nearest safe lodgings were.

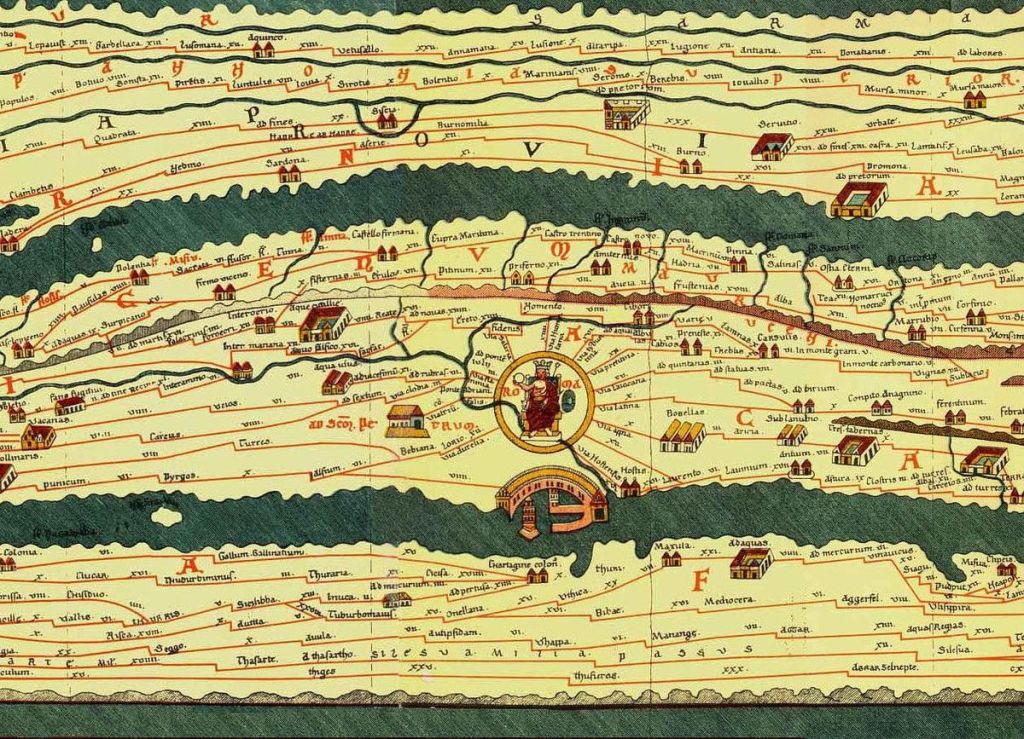

A modern map of the Roman Empire might show the it as a big blob of purple enveloping the Mediterranean, major roads snaking from city to city like veins. But for the Romans, the roads were the empire. You can see the idea very clearly in the most famous surviving Roman “map,” (more of an illustrated itinerary) the Tabula Peutingeriana, probably designed during the reign of Augustus. The map bears almost no resemblance to actual geography. Instead, its purpose is to map out the empire’s various road networks. Some historians have described it as sort of ancient subway map in how it exchanges geographic accuracy for convenience.

When the Romans visualized their empire, they didn’t think about borders between civilization and chaos. Even when rivers or walls nominally demarcated the frontier, the Romans were never particularly intent on border security. In a typical Roman garrison, the majority of soldiers would be stationed well inside the empire, supervising trade and administration. Even at the height of the empire, outsiders like Germanic tribes, often had little difficulty penetrating into Roman territory. However, once the invaders were discovered, Roman reserves positioned deep within Roman land would counterattack and destroy the attackers, who by then would be disorganized and laden with loot. It turns out there was a lot of room for shadows in between darkness and light of Rome.

In fact, very few ancient maps have any interest in laying out political ownership of land. One of the oldest known maps, for example, is the Turin Papyrus, commissioned by the Egyptians in the 19th century BCE. The map is not linear or stricty geographic. Instead, it is geological, designed for use by a quarrying expedition.

For a more modern example, look at the Reformation era Bünting Clover Leaf Map, designed to show the three main continents as a Christian clover, with Jerusalem at the center. It might look silly, but the author presumably felt that he was communicating important information about religious geography. Such examples may seem a little absurd to modern eyes, but that’s just our twenty-first century blinkers.

It is easy to forget just how recently the strictly geographically bound state came into existence. The western border between the US and British Canada was ambiguous until 1846. The Saudi-Yemeni border remained undefined until the year 2000. When you start mass-producing global maps, it just doesn’t look good to have any fuzzy bits with multiple colors.

Historical cultures, in short, used a huge variety of map types, which revealed the makers’ preconceptions about what a state actually is. Modern history books, however, take all these interesting and varied perspectives and reduces them all to the modern idea of a state with control of rigidly defined borders. In this bland, watered-down history, every culture or state is just another colored blob on the same generic map projection.

One thought on “Mapping the Ancient Roman Mind”