Some time ago, I argued that chess does not do a very good job representing the key concepts of warfare. But I might have been unfair. Today, I’m going to once again compare chess to real war, but this time I’m going to look at the parallel evolution of the two over the past few hundred years.

While the rules of chess have remained the same since the 1500s, the methods of play have changed dramatically. In many ways, the game’s evolution has mirrored that of real warfare.

The Romantic Era

In the early years of chess, players treated it less as a game and more as an art. Winning was important, but you were supposed to do it in the right way, with clever tactics and flashy maneuvers. Virtually all games began with pawns moving to e4 and e5, a simple and aggressive opening. Sacrificing pieces was highly encouraged because players believed that the initiative was more important than material superiority.

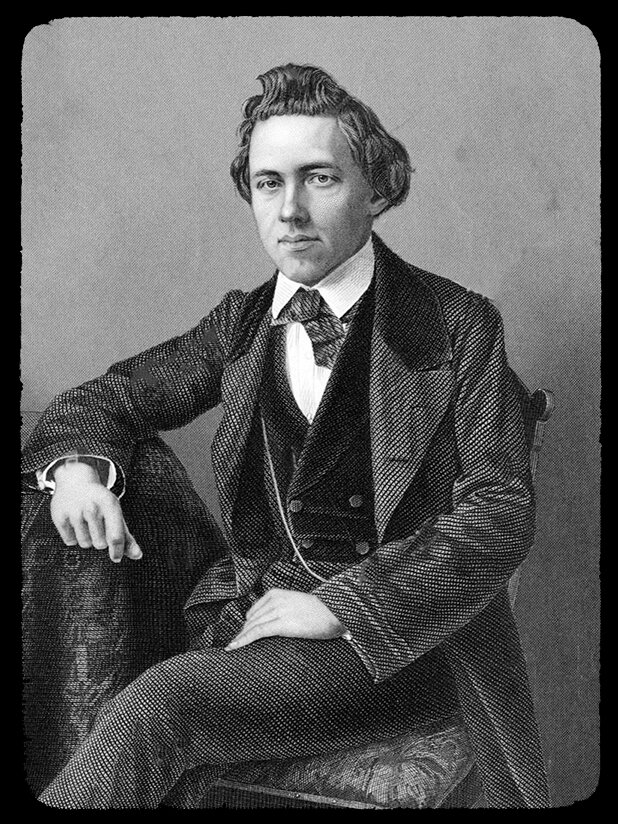

The greatest player of the Romantic era was Paul Morphy, a young American who dominated the world chess scene between 1857 and 1859. Many of Morphy’s games are still studied today for their rapid deployment of pieces and brilliant sacrificial attacks.

Another feature of the romantic chess era was that even the best players in the world were amateurs. Morphy, for example, considered it beneath his dignity to win money from playing a game, and when he became old enough to practice law, he more or less retired from chess so he could get a real job.

It’s not hard to see the parallels between romantic chess and premodern warfare, where attacking spirit, tactical maneuvers, and the initiative were paramount. One can almost imagine Morphy as a kind of Alexander the Great, a mercurial prodigy who overcame all opposition, but, in the tradition of Greek tragedy, eventually grew bored and despondent as a result of success.

Modern Chess

The romantic era of chess came to a sudden end in the 1870s when the Austrian player Wilhelm Steinitz developed a new style of play. Positional chess, as it was called, emphasized the gradual accumulation of tiny advantages, key square here, control of a diagonal there. If Steinitz captured an extra pawn in the opening of the game, he was more than happy to exchange all the remaining pieces so he could win in the endgame. This was a slow, unsentimental approach, completely different from romantic orthodoxy.

The introduction of modern positional chess coincided with a change in chess culture. By the late 1800s, the best players were no longer aristocrats or politicians. Steinitz, for instance, was an impoverished Jew. The democratization of chess meant that players no longer cared so much about the traditional romantic values. It also meant that victory and prize money had actual stakes, so players had a real incentive to play the best chess they could, even if it meant fewer flashy attacks.

As Steinitz revolutionized chess, warfare was changing in much the same way. The growing professionalization of militaries meant a greater focus on the technical side of warfare. The new approach encouraged brutal mechanized attrition. If Morphy was an Alexander the Great, Steinitz was more of a Ulysses S. Grant, a strategically-minded commander unafraid of suffering casualties in pursuit of ultimate victory.

Much like those who reviled Grant as a “butcher,” chess players were initially resentful of the new style. Adolf Anderssen, perhaps the greatest romantic player at the time, said that “Kolisch [another romantic player] is a highwayman and points the pistol at your breast. Steinitz is a pick-pocket, he steals a pawn and wins a game with it.” As late as the 1930s, the Nazis would lament the state of modern chess, and tar Steinitz as a greedy coward.

Yet Steinitz’s positional chess proved almost unbeatable, and soon all the the top players had adopted his methods.

Soon after the Steinitz revolution, one commentator summarized things rather well:

And oddly enough, championship chess has changed in the same way as has warfare, which is no longer a thing of long-distance raids, cut off from supply bases, of brilliant cavalry charges, but is a matter of “digging in” – wars now are wars of attrition. Similarly, chess masters no longer play the old-fashioned open game, having abandoned it in favor of tactics quite similar to trench warfare. This has resulted in an increasing number of drawn games – so many, in fact, that it has been suggested that the game be made more difficult by increasing the size of the board and the number of pieces.

Claude Bragdon, 1931

In the 1920s, after the mass slaughter of the trenches had disillusioned a generation, many chess players began to grow unsatisfied with the slow, attritional play of positional chess. Soon, certain players advocated a new approach, called the hypermodern school.

The hypermodern school offered a more indirect approach than positional play. Conventional positional wisdom is that control of the center of the board is essential to victory. Thus, games often turn into a battle to control a few key squares in the middle. Hypermodernists, however, argued that you could also win by conceding the center and instead controlling key spaces around the edge. At the right moment, your well-placed pieces could counterattack and destroy the other side’s overextended forces. Some later observers compared hypermodern chess to the contemporary doctrine of Blitzkrieg in the way that hypermodern masters like Alexander Alekhine could sweep away opposition without apparent effort.

Although hypermodern chess never toppled the positional orthodoxy, it remains an important part of any expert player’s repertoire.

The Present Day

Today, chess strategy has once again transformed, this time thanks to computers. Previously, the top players could endlessly debate the merits of, say, the King’s Gambit opening compared to the Queen’s Gambit opening. It an unanswerable question, like asking whether a sword was superior to a spear. But now, a few clicks will tell you that the Queen’s Gambit is 50 centipawns better. As a result, high-level chess is basically now an attempt to imitate the computer on your iPhone as precisely as possible. Perhaps chess strategy has now reached its final, objective form.

Yet while chess becomes ever more objective, computers have had the opposite effect on warfare. Military computers operate on limited information, and struggle to deal with human error and the unpredictability of conflict. Military leaders have access to more data than ever, but sifting that information is a herculean task. We may be seeing the final divergence between chess and warfare, as one grows simpler and the other more complex.

But fear not for the future of chess. While top-level play is (arguably) growing a bit sterile, the game is as dynamic as ever in the intermediate levels. Club players can borrow at will from Morphy, Steinitz, and Alekhine, mixing their styles in new ways. Military history has a tendency to overrwrite itself as weapons or tactics become obsolete, but in the world of semi-competitive chess, the lessons of the past can hold their own against the modern style. Wargamers like to imagine battles between Napoleon’s grenadiers and Alexander the Great’s phalangites. But in club chess, you can actually bring the tactics of the past to life.